Five years in production

Reflecting on my first developer job, from intern to lead developer, and all the lessons I learned at Enchères Immo.

31 December 2025 — Goulven CLEC'H

A bit of context

A turning point in my life, like for so many people, was the COVID-19 pandemic. After a breakup, and struggling to find my place in the health/social sector, I decided to switch careers and return to programming.

As a teenager, I learned Ruby to make games with RPG Maker, and dabbled in HTML/CSS and PHP thanks to « Le Site du Zéro ». Later, with friends from the RPG Maker community, we created Game Dev Alliance, where I explored web technologies (TypeScript, VueJS, Tailwind) and game engines (Unity, Godot, Ren’py). But if this was an interesting background, I lacked formal education and professional experience.

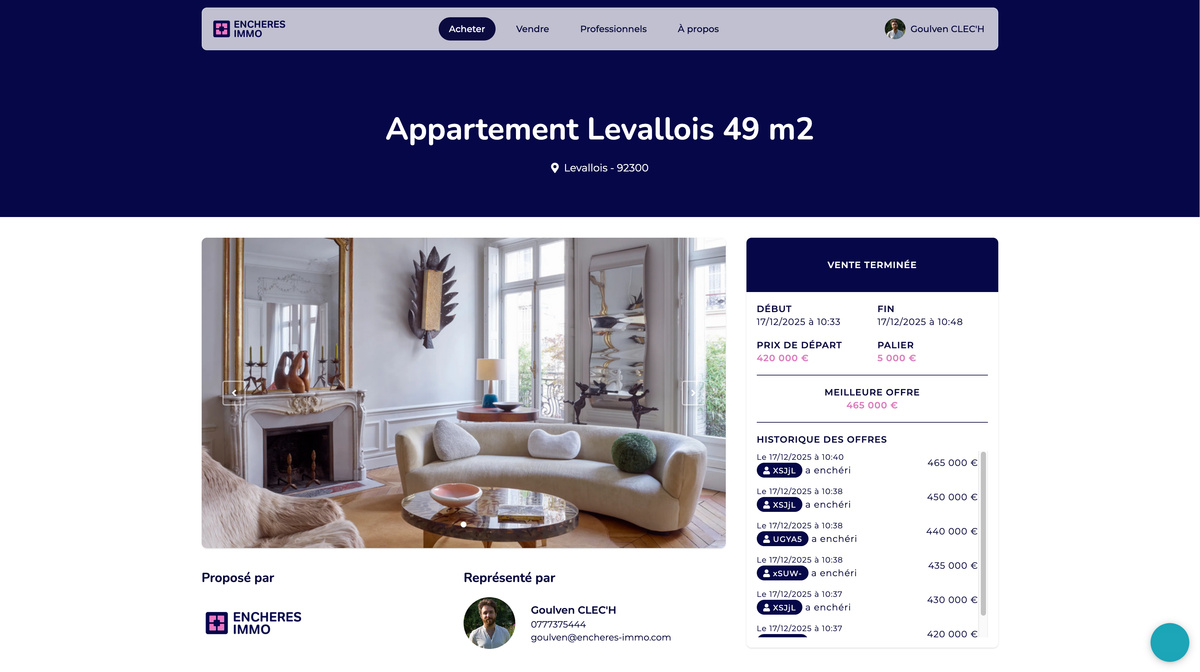

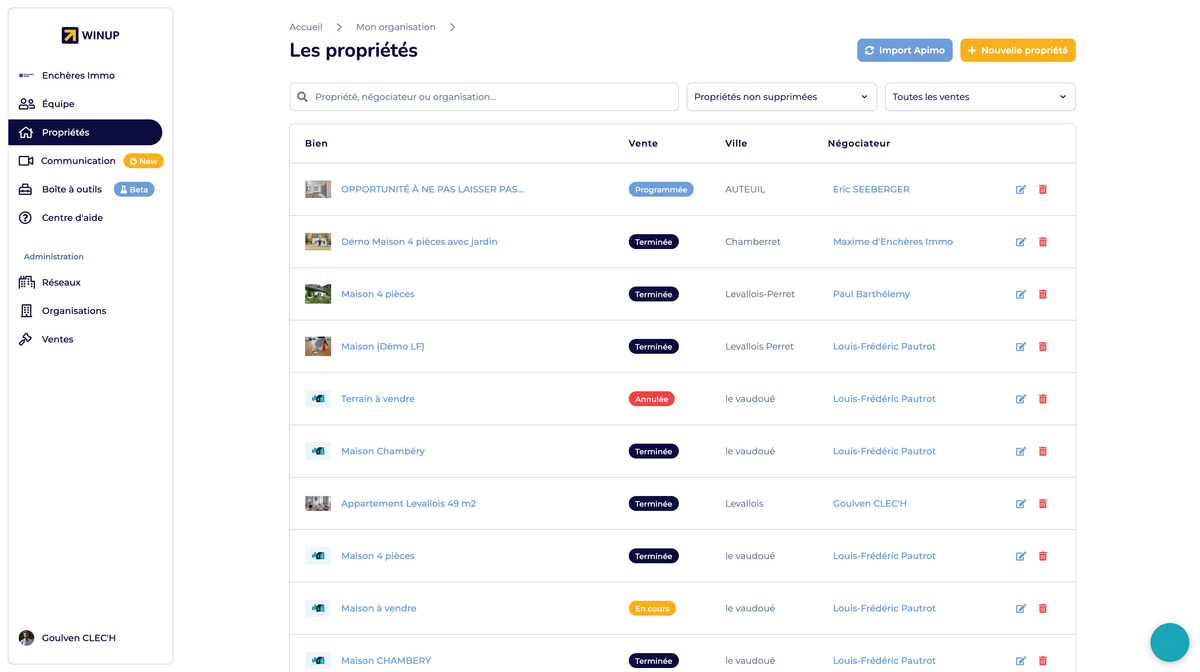

Looking for opportunities, I discovered that Le Site du Zéro rebranded to OpenClassrooms, and offered an « Application Developer » work-study program, where I spent one day per week learning TypeScript, React, and Node.js. The rest of the week,1 I joined Enchères Immo, a young startup building a real estate auction platform with Elixir/Phoenix.

But quickly, the founding engineer (and only senior developer) left the company — leaving me responsible for the entire codebase, product, and infrastructure of a live application, with real customers. All while I was still learning to trust myself as a developer, and building a work ethic in a fully remote environment.

Five years later, this tricky situation has actually turned into an amazing journey, filled with challenges, mistakes, and lessons. And as a new chapter opens for me in 2026, I wanted to reflect on everything I’ve learned during this first job.

Owning a codebase

When learning to code, « good code » felt abstract. Sure, I could tell when a piece of code was easy to read, and I quickly understood why types and documentation mattered. But the real impact of code quality, over years of maintenance, was hard to grasp on short study projects.

For instance, I overestimated « clever » code, complex abstractions, elaborate design patterns, and cryptic optimizations. This bias may have come from coding challenges, interview prep books, pop culture hackers, tech influencers selling courses… and perhaps my own ego.2

On the contrary, I completely underestimated how code is a disposable artefact. When owning a codebase long-term, you constantly explore, change, extend, and discard code. After a few years, most of the original codebase has vanished, but the need for malleability never fades, driven by new features, bug fixes, and evolving business needs.

That’s why, I now value simplicity, idiomaticity, and expressiveness as quality indicators. In Elixir, that means embracing pattern matching, immutability, and OTP conventions. It means avoiding unnecessary abstractions, and writing small single-purpose functions, well-structured modules with clear boundaries, self-descriptive names, and comments that explain why rather than how.

But simplicity doesn’t mean avoiding architecture. When we needed to connect multiple industry-specific CRMs—each with different APIs, data formats, and quirks—I built a system using Elixir behaviours, background workers, and adapters. It sounds complex, but it’s actually idiomatic and expected by any Elixir developer, as it makes adding or removing integrations straightforward, with minimal risk of breaking existing ones.

Test and observability

To truly make my codebase malleable, tests were the superpower I lacked. When I took over, only the core domain had partial coverage. Overwhelmed by my new responsibilities, I neglected testing for months, ignoring a constantly red CI.

Of course, this came back to bite me. Bugs crept in, development slowed down, and refactoring became a nightmare. So I learned to test properly, focusing on critical paths first, on business behaviour and edge cases, not implementation details.

The coverage still isn’t perfect today, but a solid test suite gave me the confidence to refactor continuously, as most regressions were caught early. Tests also serve as living documentation, so I don’t have to document every business rule and edge case by text.

Observability was the other game changer. At first, just keeping logs was a big improvement. Then, APM tools like AppSignal brought Slack alerts for errors, and worked beautifully with Erlang’s « let it crash » philosophy. Combined with a « job health » script by ![]() Clément Uster monitoring background workers, we caught issues before users did.

Clément Uster monitoring background workers, we caught issues before users did.

Thanks to tests, error alerts, and logs, I gained peace of mind, and so productivity and confidence. When a user reported a « bug », I could quickly identify whether it was a real issue, a third-party failure, or simply a misunderstanding on their side.

Tech debt management

Tests became my main lever for managing technical debt. Updating dependencies turned trivial: run the tests, check for regressions, merge. Refactoring old or poorly designed code felt much safer, even when I didn’t fully understand the original intent.

After completing our major folder structure refactoring, I generally avoided big rewrites. Instead, I adopted the Boy Scout rule, always leave the code a little better than you found it. Every time I worked on a module, I’d try to improve its readability, tighten its structure, or add missing tests.

Nevertheless, two significant pieces of technical debt remain. Before my arrival, the original developer chose Pow, the only mature library back then for authentication, and Surface, for component-based LiveView development. But over the years, both slow down our Phoenix/LiveView upgrades, and make maintenance harder. Today, Pow is hardly maintained, in favor of the official phx.gen.auth, and blocks the upgrade to Phoenix 1.8 entirely. Surface on the other hand has seen most of its features land in LiveView itself, but leaving will require rewriting all our components.

These dependencies illustrate a painful lesson: the more critical a dependency becomes, the harder it is to replace, even as its drawbacks grow.

Shipping features

A malleable codebase means spending less time on bug fixes and maintenance, and more time doing your job. But delivering features consistently required more than clean code. For me, I mainly built around two pillars: routines (like my morning coffee) to maintain focus in a remote environment, and iterative work, breaking every ticket into small tasks (less than a day of work each).

To make that iterative process possible, feature flags became essential for shipping partial or beta features safely, while our CI/CD pipeline acted as a safety net–running format, lint, static analysis, and tests on every push. With these tools, I became more consistent and confident in tackling tasks, and I saw my productivity slowly improve over the years.

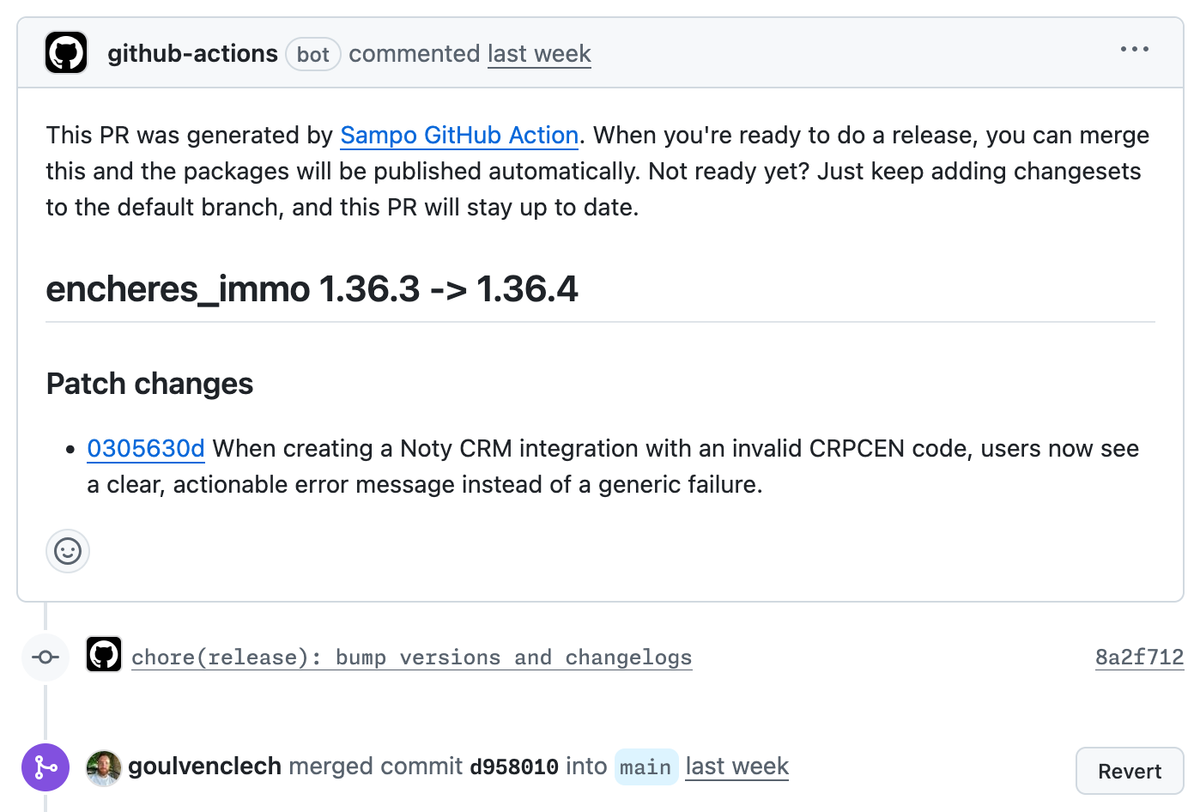

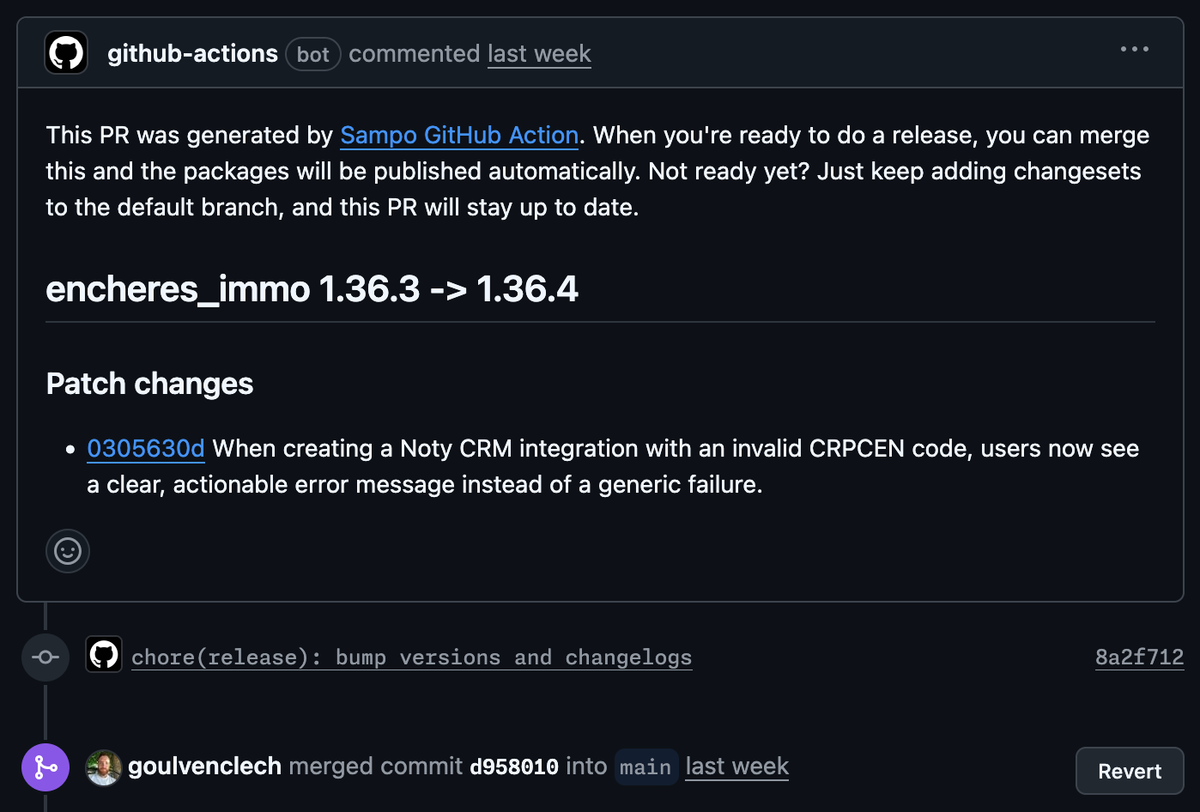

And to ship my work, my side project Sampo transformed our two-week release cycle into multiple releases per week. For each new commit or pull request, I simply add a changeset (markdown files describing changes explicitly), and Sampo automatically opens/updates a release PR,3 and deploys the current main branch to a staging environment. When merging the release PR, Sampo creates a new GitHub release, updates changelogs, and deploys to production. No more staging branch, no more manual changelog or deployments.

Understanding stakeholders

Thanks to all those tools and automations, I could focus on building features, but not just coding. Especially in a startup like Enchères Immo, and even more since the AI boom, my responsibilities shifted to translating stakeholder needs into technical solutions: funders,3 sales and CSM teams, clients, third-party vendors.

This meant regular communication with non-technical team members, understanding their pain points, and aligning development efforts with business goals… But not doing everything stakeholders ask for! I learned to challenge requests, dig into underlying problems, and propose better solutions. You can often find a « good enough » solution that solves 80% of the problem with 20% of the effort.

Owning the product means learning to say no, or at least « not now ». There’s always something urgent, always a new request, and I needed to prioritize work.4 And when priorities weren’t clear, I could turn to the founders for guidance.

That said, one mistake I never fully solved was tracking feature usage. We lost time building features that were barely used, or only by one client, and I should have measured usage and promoted new features more actively.

User experience

I’m neither a web designer nor a UX expert, but user experience became a constant concern. Real estate agents aren’t always tech-savvy, and buyers are typically one-time users who need to understand the platform immediately.

Without a dedicated designer, I drew inspiration from Tailwind UI and shadcn/ui, built reusable Surface components, and enforced stable design rules (colours for actions only, predictable layouts). All this created a common language across the product, hopefully making it more intuitive.

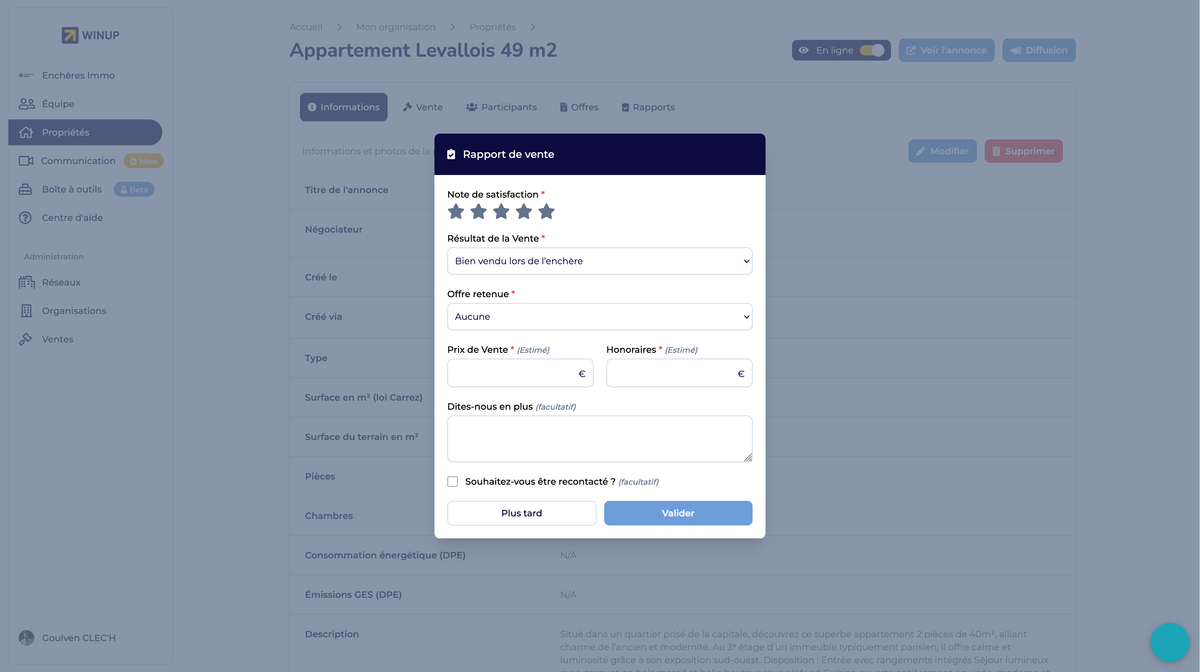

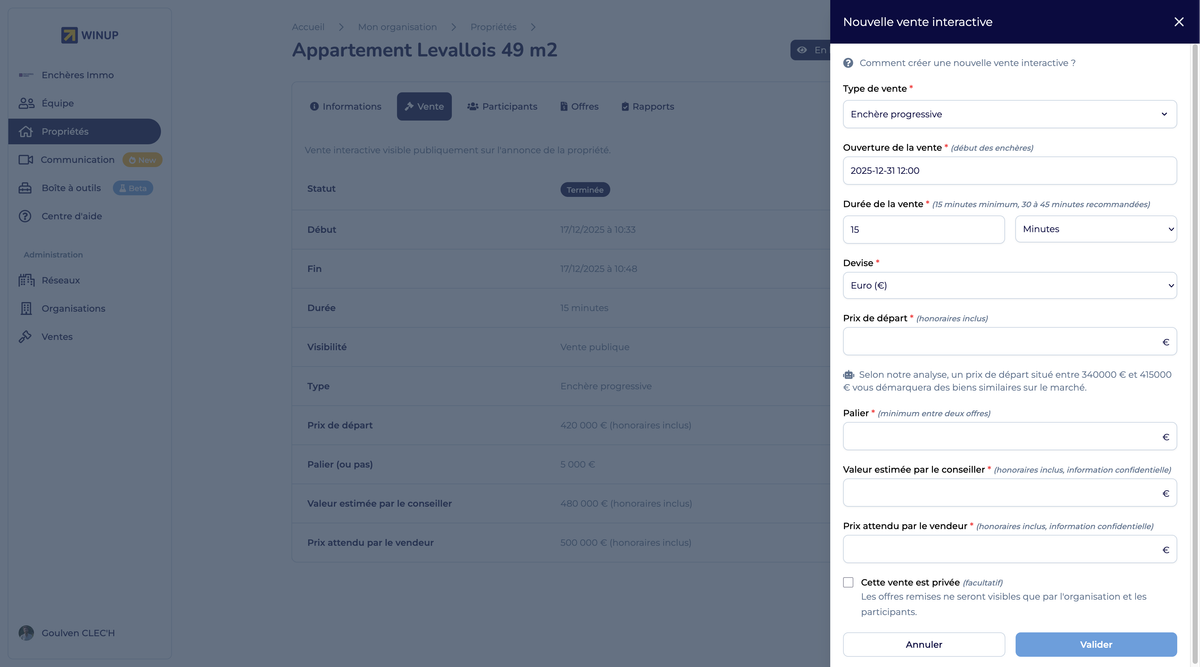

Our sales team’s constant demonstrations to potential customers became a key advantage. Combined with feature flags and our rapid release cycle, we could gather feedback early, and catch issues before real sales. After these initial tests, we could gradually roll out to everyone.

Wrapping up

There’s still so much to do at Enchères Immo, but after five years, I started to feel the need to move on.

One of the recent setbacks was the political crisis in France, which shook real estate actors’ budgets and growth plans. While we managed to stay afloat, as competitors closed down, it meant postponing team expansion indefinitely. And with limited growth opportunities, the fatigue of working alone weighed heavier than before.

When new offers came my way, I felt it was time to explore new horizons. I wanted to stay with Elixir/Phoenix, but perhaps try the other side of the spectrum: a larger team, more structured processes, real scaling challenges. Maybe I’ll miss the autonomy and end-to-end ownership, but in the first roles of your career, I believe it’s important to explore what truly suits you.

Hiring my replacement

Given our past struggles to recruit experienced Elixir developers, and seeing the founders weren’t available to lead the process, I took it upon myself. I wrote a job description emphasizing autonomy and end-to-end ownership, posted it on LinkedIn, the Elixir Forum, and Elixir Jobs, and quickly received around forty applications. After filtering and ranking candidates,5 I shortlisted eight profiles for screening calls.

The technical exercise was a small Elixir/Phoenix/LiveView project—user authentication, seed scripts, external API integration, scheduled jobs, and a UI built with Surface and Tailwind. The goal was production-ready code: clean modelling, proper testing, good error handling, clear documentation. After reviewing exercises in technical interviews, I narrowed down to four candidates and handed off to the founders for final fit interviews. The whole process took about three weeks on my side.

Technical handover

Before those last weeks, I hadn’t truly realised how much knowledge lived only in my head. Backlog priorities, third-party quirks, infrastructure details, design decisions… I had to write a lot of new GitHub issues and expand our Markdown documentation. Tedious, but necessary.

I also took the opportunity to update most dependencies and tackle some lingering technical debt, hoping to give my replacement a cleaner slate. Together with the two co-founders, we discussed upcoming priorities, what I should focus on before leaving, and what could serve as good first tasks for the new developer.

Instead of feeling drained by the prospect of leaving, those final weeks turned out to be some of my most productive, and I’m proud of the state I’m leaving the codebase in. And of course, I’ll be available for questions and urgent help for the next few weeks.

Final thoughts

Looking back, it’s clear how badly things could have gone. Leaving a junior developer responsible for a production application was a risky bet… and there were definitely low points, mistakes, and moments of doubt. Yet I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished, and grateful for the opportunity. What a way to start a career!

If I could advise my 2020 self, I’d say to believe in yourself, take ownership, build rituals, and stay consistent. I also learned two key lessons: a developer’s value skyrockets when you bridge the gap between technical and product concerns; and software quality is ultimately about shipping better features faster, without the fear of breaking things.

In 2026, I’m moving on to new challenges. Still with Elixir/Phoenix, but part of a larger international team, in a remote async environment, with serious scaling/compliance stakes… I can’t wait to see how I grow from there.

I wish nothing but the best to Enchères Immo, and I’m excited to see how their product and team evolve in the coming years.